There’s an interesting story to how studio sessions, concerts, a recording, and the writing and publication of a book have shaped performances of Pat Metheny’s music by the trio Transcendence

This is a story of a set list. A set list is the order of compositions to be played in a concert. At some concerts, audiences may have in hand a printed list, although that’s a practice in only some kinds of musical settings. In most, the performers have a copy of the list taped to an instrument or speaker cabinet. The performers in Transcendence are Bob Gluck (keyboards), Christopher Dean Sullivan (bass), and Karl Latham (drums). Our new album, Transcendence Plays Music of Pat Metheny (FMR Records) can be found on BandCamp and, starting July 1, on streaming platforms. Another version of this essay can be found on my Substack blog, Music and Our Lives.

I have spent a fair bit of time designing set lists, often going back and forth about what it might include. Sometimes, there’s a theme. For me, this is most often the case only following the release of a book or recording, the theme is set, and the question is how much of the show should be devoted to that repertoire, and then, which compositions and in what order.

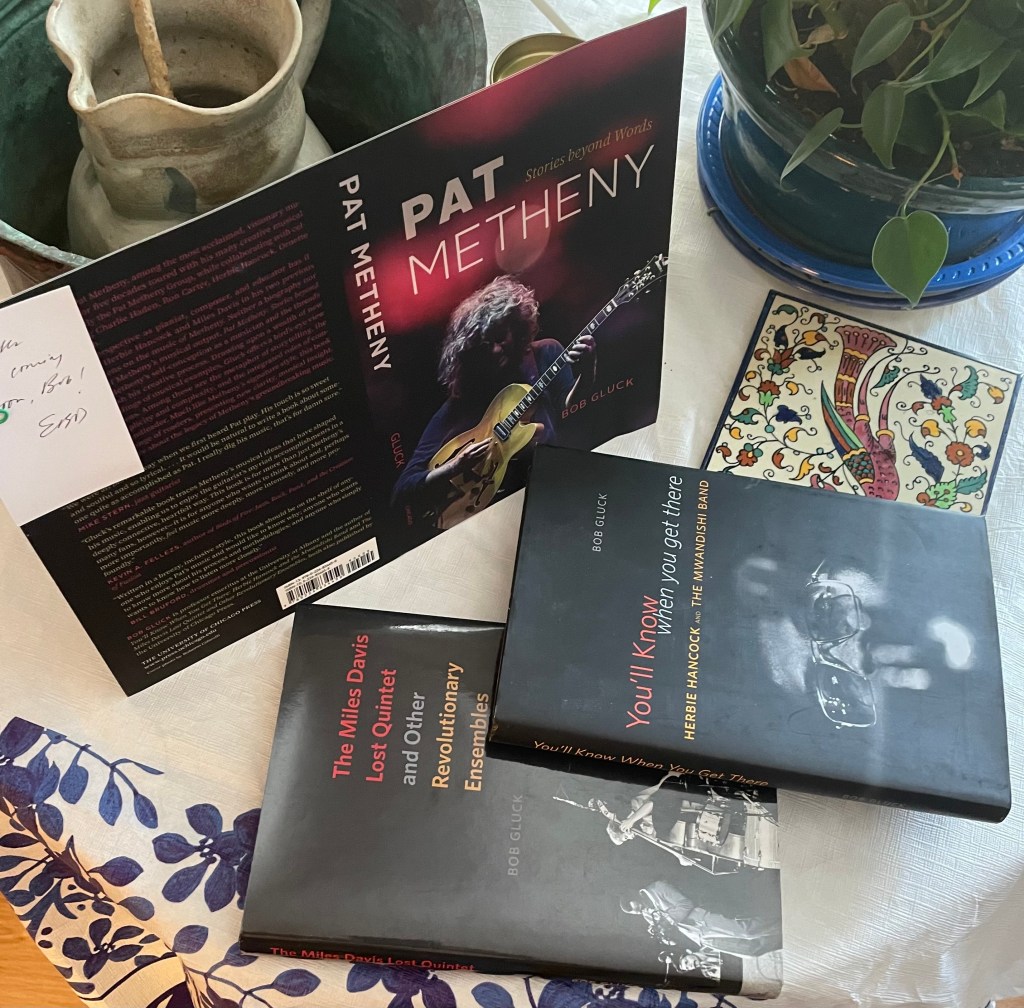

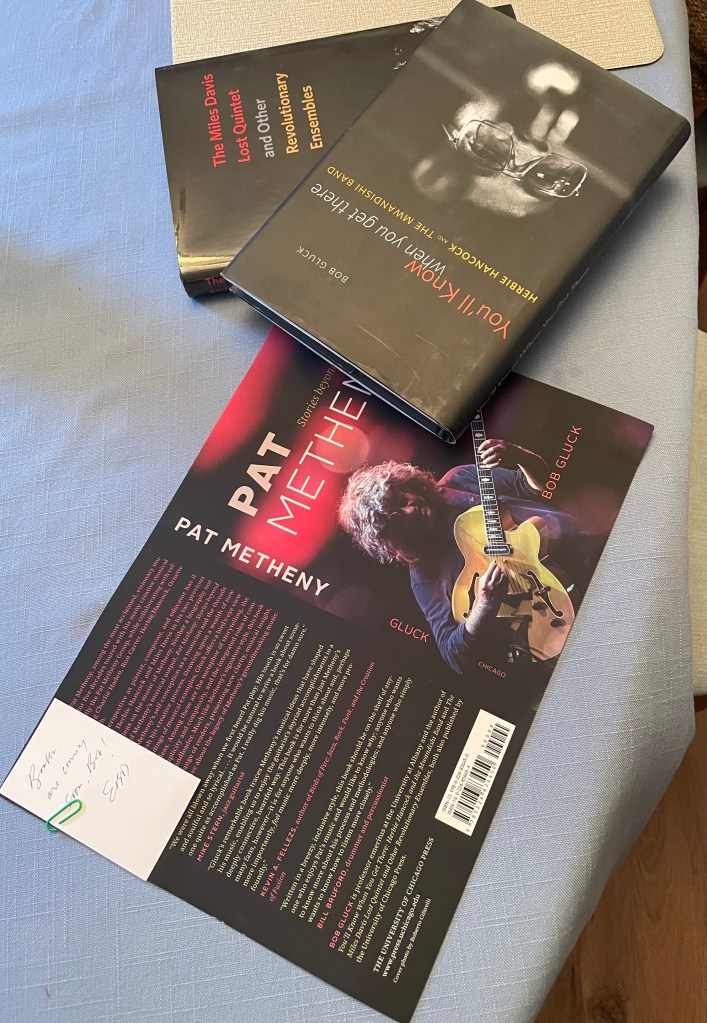

Following the release of my book Pat Metheny, Stories beyond Words (University of Chicago Press, August 2024), my thinking about how to design sets of his music has been guided by a combination of what the band and I have enjoyed playing, and whether there are notable musical ideas within compositions that could be exemplified in performance. Finally, of course, comes the question of the order of the pieces within the set, and with that, many of the kinds of factors that most musicians who construct set lists think about. Are there groupings or combinations of compositions that might form an interesting “sub-set” or suite, is there variety in mood, energy levels, tempo, types of feels and such things? Often, the answers can be quite intuitive. Also, building set lists on the same theme or repertoire can, over time, take on a certain momentum of its own.

It wasn’t part of my plan to become engaged in a Pat Metheny themed project or, rather, projects. What initiated all of it was an unexpected event in late March 2019, six years ago. One evening, I was chatting with Metheny following a Side-Eye trio concert. Some of you will respond to what I’m about to say with “Bob, really?” but at a certain point, I told him that it was getting late for me, so I’d better head home.” As we saif goodnight, he paused, and said “wait a minute,” looked around, and handed me a copy of his newest “Songbook.” This initiated a really interesting, albeit unanticipated six-year ride. Back in March 2019, I had no idea that any kind of projects might unfold. I was working diligently on other things at the time and I didn’t yet know that some of them would go on pause, stop, or morph due to the coming pandemic.

Meanwhile, I was rehearsing my own music, preparing to record what became the album, Early Morning Star. When I took a break from working on that, I would played my way through the Metheny Songbook, one or two tunes at a time.

By late summer 2019, I had chosen 25 Metheny tunes that most interested me as a performer. Many of them required serious translation for piano and bass, and then a piano, bass, and drums trio. I invited my longtime bassist compatriot Christopher Dean Sullivan to play a duo show at my university. I realized that my list of 25 needed to be cut to 15 (or so). We rehearsed a few of that final 15 in mid-November and played the show in late January 2020. That date tells you something about where this is heading.

Planned concerts on two other projects were cancelled for that Spring. My new album, Early Morning Star (with Andrea Wolper, Kinan Azmeh, Ken Filiano, and Tani Tabbal) was released by FMR Records on June 15, 2020, so much of it would never be performed in front of an audience or not with all the same band members. Somehow, performances with the Metheny repertoire continued through the end of 2020.

Here’s what the January 28, 2020, piano-bass duet setlist looked like:

Are You Going With Me (Metheny)

80/81 (Metheny)

Offramp (Mays and Metheny)

Always and Forever (Metheny)

Afternoon (Metheny)

Back Arm and Blackcharge (Metheny)

The Bat (Metheny)

Roof Dogs (Metheny)

Another Life (Metheny)

Dream of the Return (Metheny)

Half Life of Absolution (Metheny and Mays)

Farmer’s Trust (Metheny)

Question and Answer (Metheny)

James (Metheny)

The hour and a half set included fourteen compositions, leaving out two that had been rehearsed, Everything is Explained, from Pat Metheny’s newly released album, From This Place, and the one non-Metheny piece, Herbie Hancock’s I Have a Dream. A few months later, I’d ask Pat to send me the score to the complex opening piece, America Undefined, from his new album. This became my entry point for the book.

I had already accepted an outdoor show for September 3, 2020. Chris recommended Karl Latham to join as drummer to make it a trio. This proved to be an excellent choice. Chris and I had one socially distanced rehearsal in early June. I started to make video recordings of some of the music played solo, a month later, and in late August, the trio gathered at Karl’s studio for the only trio rehearsal we’ve ever had. The chemistry was immediately apparent and playing the music, some of it quite challenging, came naturally and with enormous spontaneity.

During this period, the “staples” Chris and I worked on were the upbeat Afternoon, the ballad The Bat, and the driving Question and Answer. The latter was a tune that Metheny first recorded with a trio, so we knew it could be a great vehicle for us. I added one more non-Metheny tune, Keith Jarrett’s beautiful Everything that Lives Laments, from his “American Quartet” of the 1970s. Now, with the addition of Karl, we went more intensely at some of the fierier works within Metheny’s repertoire, Half Life of Absolution, Offramp (each composed by Metheny and Lyle Mays), and Roof Dogs (from Pat Metheny’s Unity Band).

Here is the set list from early September 2020 trio show. Note that we never rehearsed most of these tunes as a trio, although Chris and I had played them as a duo several months prior. This netted five ballads, two “medium” tempo, four up tempo, and then Half Life of Absolution. The latter was the toughie, a wonderful suite of changing moods, wailing melodies, rich harmonic changes, and long periods of relative stasis. To say the least, this was an eclectic Metheny set list.

*Farmer’s Trust (Metheny)

+Afternoon (Metheny)

+Are You Going with Me (Metheny)

*Everything that Lives Laments (Jarrett)

Offramp (Mays and Metheny)

*Always and Forever (Metheny)

*Another Life (Metheny)

Roof Dogs (Metheny)

*The Bat (Metheny)

80/81 (Metheny)

Half Life of Absolution (Metheny and Mays)

Question & Answer (Metheny)

This list may look long, but it didn’t even include everything I initially imagined including. There were four more charts in the wings, widely ranging Metheny tunes: the ballads New Year and Dream of the Return, plus Counting Texas and the hands-bending Back Arm and Blackcharge. The set should have put to rest anyone’s generalizations about Pat Metheny’s body of work. Yes, melodious; yes harmonically rich; and also yes at times aesthetically close to Ornette Coleman; yes, yes, and yes, and yes.

We subsequently decided to continue working together, with social distancing. Karl had started a weekly live stream series called “Concerts From the Cabin.” We played two of those shows. In late October we mixed and matched music by Pat Metheny, Chick Corea (Spain), Herbie Hancock (I Have a Dream, and Dolphin Dance), Joe Zawinul (A Remark You Made), and Keith Jarrett (Death and the Flower, also from the American Quartet). Only one of pieces was my own, Not for Today (from my album that had been recently released). Only two of the ballads and medium tempo compositions on the set list were by Pat Metheny. His music was more strongly represented by three intense, fast-moving compositions, Offramp, Back Arm and Blackcharge, and the multi-section Half Life of Absolution.

Offramp (Mays and Metheny)

Question & Answer (Metheny)

Back Arm and Blackcharge (Metheny)

*The Bat (Metheny)

Half Life of Absolution (Metheny and Mays)

This session proved to be important for our trio, for two reasons. First, on my drive home, I pondered what I was learning about the music from playing it. I decided to ask Pat Metheny what he thought of the idea of my writing a book about his work. On November 17, he agreed to it.

Second, and (hopefully) also long enduring, it was material from this session that would later appear on the new album, Transcendence Plays Music of Pat Metheny (FMR). That album drew upon a high-quality multi-track recording from that broadcast, something we only later discovered. After months of selecting, mixing and mastering, it is now available on BandCamp (and has a release on streaming platforms on July 1):

The trio performed a second remote, live stream concert in mid-December. Five of the tunes on the set list are from or adjacent to the Metheny repertoire:

*Death and the Flower (Jarrett)

Half Life of Absolution (Metheny and Mays)

Question & Answer (Metheny)

Back Arm and Blackcharge (Metheny)

*A Remark You Made (Zawinul)

This time, we opened and closed with ballads, neither by Metheny, but within a related musical world. They bookended two Metheny scorchers, with the most straight-ahead tune (by Metheny) placed in the middle. I’m leaving off this list other selections that are’t relevant to the Metheny theme.

Exactly one month later, in mid-January 2021, Pat Metheny and I began what would turn out to be three years of dialog about his music and its context. These conversations addressed some of the streams of thought that are treated in the book. Overlapping with these were my own close listening and reflecting on what I gleaned from performing and looking in great detail at the music, and interviews with other musicians who have been involved in the past couple decades of Pat Metheny’s career.

My attention in March-May 2021 was divided between composing and rehearsing new compositions of my own, and dialoging with Pat Metheny (which continued through June 2023), as I worked on the book. I had begun to scale back my university teaching schedule, as I headed towards my retirement in August 2022. Once my final semester of teaching concluded, I dove into making video recordings, at home, of solo versions (sometimes multitracked keyboards, but introducing electronically processed hammered dulcimer, an instrument I was learning to play. The sessions in August-September included these compositions, none of which had appeared in any of the duo or trio concert set lists. With the exception of the rip roaring “Everything is Explained,” the series focused on more aethereal works, the latter two being ballads:

Imaginary Day (Metheny and Mays), a tour de force work of changing moods and aesthetics

Across the Sky (Mays)

New Years Day (Metheny)

Meanwhile, I realized that I had made enough multi-track keyboard solo recordings of several of my own new music to comprise an album. “And every fleck of russet” was released on January 1, 2024 (Electricsongs Records, and available on BandCamp). By this point, I was working on the final, production stages of the book Pat Metheny, Stories beyond Words, which was published byUniv. of Chicago Press in August 2024.

The release of the book opened up new opportunities to regather the trio. At this point, we had secured a record label (FMR Records), and entered the final production and release stages of the forthcoming album.

The logic behind our set lists in late September and October 2024 balanced music that exemplified core ideas I discuss in the book with the usual considerations in putting together a show. Again, I mark the ballads with an * and medium tempo compositions with +. The others are the mix of up tempo, and intense and free ranging. By this point, the set list had become relatively stabilized (although who knows what the future may bring).

Here’s the September 2024 set list:

*The Bat (Metheny)

+Afternoon (Metheny)

*Always and Forever (Metheny)

Roof Dogs (Metheny)

Question & Answer (Metheny)

Offramp (Mays and Metheny)

The October show represented a challenge because Christopher Dean Sullivan couldn’t make the date. We rejected the idea of subbing another bassist for Chris and instead, performed as a Bob and Karl, keyboards-drums duo. I added to my setup an addition keyboard on which I periodically filled in bass lines. I also added arpeggiation to the piano patches on Half Life to increase the density level, and I pre-recorded some material to add vamps to Roof Dogs. Here’s the October set list:

+Afternoon (Metheny)

*Always and Forever (Metheny)

*Farmer’s Trust (Metheny)

Half Life of Absolution (Metheny and Mays)

Question & Answer (Metheny)

Roof Dogs (Metheny)

These post-book release set lists were shorter, aiming for representation rather than completeness. This length also could allow time for discussion about Metheny’s musical ideas. The 2024-2025 set lists to date have been pretty consistent.

Afternoon represented the breezy side of Metheny (with some complicated turns embedded within it). Always and Forever reentered the sets to exemplity a central musical idea of Metheny as composer. This is the use of long, stepwise bass lines juxtaposed with seemingly simple, slowly evolving chords that gain complexity and nuance as the bass line moves. This is part of the “secret sauce” that enables what I call in the book long “narrative arcs” in both the composed sections and the kinds of improvisation towards which Metheny often strives.

I knew that we could treat the ballads, Farmer’s Trust , The Bat, and Always and Forever in our own personal, emotive manner. Question and Answer, and Roof Dogs have served as vehicles to display the dynamism of the trio – the way we listen closely and responsively to one another while maintaining forward motion. Offramp would represent our most free-for-all, open improvisation. Roof Dogs could also trend in that direction to varying degrees. The only composition that was introduced on the first (bass-piano duet) set list, but didn’t continue onward, was James. I didn’t feel that we had anything new or personal to add to its life in the world.

The reality is that we treated every one of the tunes as potential “grist” for the “mill” of our inherent spontaneity as a band. What really unifies our performances is the collective personality of the band as we treat music by Pat Metheny.

The release date for the new trio album was guided, in part, by the reality that all three of us had other projects headed towards completion and publication. In January 2025, Karl Latham’s Living Standards II (with Mark Egan, Mitch Stein, Henry Hey Roger Squitero, and Wolfgang Lackerschmid) would be released on Drop Zone Jazz Records; and an expanded and updated paperback edition of my book The Music World of Paul Winter was set for release by Terra Nova Editions in mid-March. Karl has another album coming in September 2025, and Chris has now recorded his own that is nearing readiness for production.

Thus, we set a pre-release date for Transcendence Plays Music of Pat Metheny for May 2025, with streaming available in July 2025. Putting together a schedule that allowed sufficient space for each of these releases was like threading a needle.

In mid-May 2025, the trio performed another concert. This set list leans in the direction of ballads, adding one mid-tempo piece, and a few compositions that move at a rapid clip.

*The Bat (Metheny)

Offramp (Mays and Metheny)

*Always and Forever (Metheny)

Question & Answer (Metheny)

+Afternoon (Metheny)

*Farmer’s Trust (Metheny)

Roof Dogs (Metheny)

Next up, on July 1, comes the streaming release of the trio album, Transcendence Plays Music of Pat Metheny. Do give it a listen! You can do so now, by “taste testing” and purchasing downloads on BandCamp (the CD is available through BandCamp, Squidco, FMR, and other outlets). The best way by far to support an artist’s work is to make a purchase (which you will then own) rather than only stream, which becomes an option in July.

We’ll see where the trio and its set lists head in the future. I imagine future lists responded more to the newly released recording than to the book.

If you would like to see a straight chronology of this narrative, You can find it, without this commentary, in my previous post. You can find more performance videos of the trio from 2024-25 on YouTube. There are three relevant playlists.

Posted in great musical thinkers, Memories of shows, Pat Metheny, playing the music

Tags: christopher dean sullivan, FMR Records, herbie hancock, improvisation, jazz, jazz duo, jazz trio, Karl Latham, keith jarrett, live-performance, Lyle Mays, music, musical performance, Pat Metheny, piano trio, set-list, University of Chicago Press, Zawinul